This is the low-bandwidth, text alternative to the video Myeloma and the kidney, from the post Myeloma and the kidney.

Neil Turner – Nov 2020

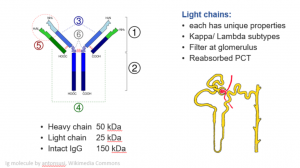

The things that myeloma can do to the kidney; it’s quite selective but it’s the most photogenic part. Here is a picture of an immunoglobulin molecule on the left and on the right a bit of kidney.

What do you think of it?

Click here for larger image

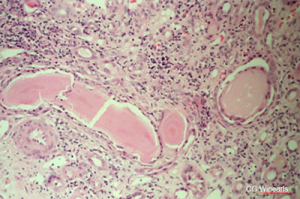

The glomerulus looks good, but the interstitium does not. There are not back-to-back tubules here, there are masses of invading cells, and here in this rather dilated tubule is a funny-looking cast with lots of cells around it. This is quite characteristic of light chain coming out of solution and aggregating in the tubules to form these casts.

Click here for a larger image

The immunoglobulin molecule, you’ll remember, has two heavy chains and two light chains. The whole molecule weighs about 150,000 Daltons (150 kDa), and of this each heavy chain is about 50, and each light chain is about 25 kDa.

At the tops of the ‘Y’ this part of the heavy chain and this part of the light chain have a variable region that binds to the antigen. It means that each antibody is completely unique. Its chemical properties are altered by the structure and sequence in this region. That’s really important and it helps to explain why only some cause the pathology that’s characteristically associated with myeloma. The light chains come in two different sub-classes, kappa and lambda.

As they’re only 25 kDa, light chains filter freely at the glomerulus and pass into the filtrate in Bowman’s capsule. As the filtrate passes along the tubule lots of things are reabsorbed, including lots of water, and they become more concentrated. Small amounts should be reabsorbed as well in the proximal tubule, but if there is overproduction they overload the re-absorption mechanisms for small proteins. When that happens, they travel further down the nephron and there’s a risk if they have the right physicochemical properties, and in circumstances of dehydration or maybe exposure to certain drugs (loop diuretics?) they may come out of solution, aggregate, and form a cast like you saw above.

Light chains can

|

Myeloma can

|

So light chains can aggregate and form casts, but only some light chains do this. Other light chains may aggregate to form amyloid fibrils and cause amyloidosis, which is a different phenomenon altogether. Others when reabsorbed into tubular cells may cause damage directly. Sometimes you can actually see evidence of it, for instance, crystals forming and aggregating in the cells. But sometimes the evidence is just that there seems to be renal impairment – harder to prove. Rare light chains may be able to do more than one of these things.

Myeloma can upset the kidney indirectly too. Hypercalcemia notably causes you to become dehydrated and worsens your kidney function. Any malignancy, particularly a hematological malignancy, where the cell turnover is very high, can generate lots of urate from metabolism of purines. That’s more typically seen after chemotherapy and that’s why we give allopurinol or other prophylaxis to patients we are about to give chemotherapy, particularly in that first cycles of treatment to try and prevent that from happening and urate nephropathy is when large amounts of urate pass into the tubules and crystallize in the tubule and form a crystal nephropathy and acute kidney injury.

So here again is a slide of a myeloma:

Click here for a larger image

Myeloma cast nephropathy, with these very pink homogeneous unusual looking proteinaceous casts fractured here, which is sometimes a characteristic feature of them. But more typical is the cellular reaction around many of the casts that you can see here. There isn’t a glomerulus in this slide but if there was, it would look normal and it’s actually quite difficult to make out any tubular outlines at all. So typically this happens in response to dehydration, infection, some kind of stress, possibly contrast injection. The very first reports of what was described as contrast nephropathy was seen in patients with myeloma. It may be very difficult to reverse if the kidney looks like this, with extensive destruction.

Click here for a larger image

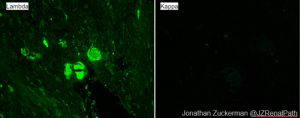

Immunofluorescence can help you sometimes not all casts bind it. But on the left you can see that this particular patient had lambda light chain cast nephropathy, indicating that it’s a monoclonal protein problem.

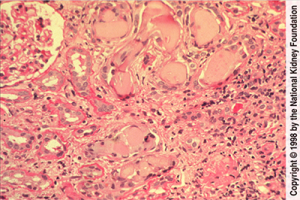

Here’s another example:

Click here for larger image

This one does show a normal glomerulus on the top-left. Again, the cellular reaction around the casts, and again, the very classic appearance of the casts. So how are you going to suspect that your patient has myeloma?

Tests in myeloma

- Anaemia

- High calcium

- Increased serum total protein

- Protein in urine

- May react poorly with sticks; much lower ACR than PCR*

- ‘Bence Jones’ protein – but now detected immunologically

- Kappa/Lambda ratio

* Typically 70% glomerular prot is albumin

This is an interstitial disease, so like other interstitial diseases, rather hard to identify. But often the patients are unwell because of the bone marrow disorder. They’re very likely to be anaemic with sometimes low cell counts in the other lines as well, platelets and white cells. I mentioned the high serum calcium, which will contribute to the renal impairment. It’s not universal, but it’s incredibly helpful and one of the useful aphorisms in kidney medicine is patients should have a low calcium in acute renal failure and certainly in early chronic renal failure too. So if you see a patient with even a high normal calcium, you should be suspicious that the calcium might be a clue to an underlying disorder.

If you measure the total protein of the patient and take away the albumin you may find that there’s an increased total protein in the blood that could be accounted for by increased immunoglobulin levels. Of course you can measure immunoglobulin levels directly too, and do electrophoresis to see whether there is an overgrown clone secreting a complete immunoglobulin (an M band). But patients sometimes have only light chain production, and therefore the protein in the urine is going to be a better test for the nephrological diagnosis.

The catches are that Bence Jones protein (meaning light chains from an immunoglobulin) may react poorly with dip sticks. You can use these different behaviors usefully: if you measure albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR) and protein:creatinine ratio (PCR) and see a big difference between them. Typically, if you’ve got more than about gram of protein in your urine (PCR 100), albumin should be around 70% of it. If it’s a lot less than that, it suggests that you’ve got an abnormal protein in your urine or tubular proteinuria.

The original Bence Jones protein test relied on behaviour on heating with acid. Now it’s detected much more reliably and at a lower level by immunolofixation tests that quickly can tell you which sub-type of light chain it is.

A highly sensitive test measures light chains in blood. The ratio of kappa to lambda chains is useful because renal failure reduces your excretion. So naturally the levels of light chains in your blood rise with renal impairment, but if you’re over producing one of them, the ratio will be distorted at any level of kidney function. That’s a test that usually has to be sent away and takes a while to come back. The modernised immunological test for urinary Bence Jones protein is the way you would probably get back first.

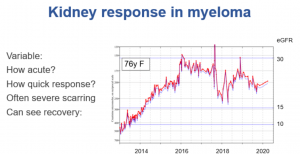

Now you might be quite surprised having seen those biopsies that you can get much recovery from casts nephropathy in myeloma. But you can sometimes, here’s an example.

Click here for a larger image

This 76 year old woman presented in 2013. She had very severe renal impairment at that time, so severe and for many months, leading us to create an arteriovenous fistula ready for haemodialysis. As you can see, seven years later it had still never been used. Her myeloma responded very well to treatment, and that must have helped her kidneys recover over the next three to four years. They then stayed pretty stable but with an eGFR about 25 for 2 years, and then you can suddenly see a drop in function again when her myeloma relapsed, again successfully treated. She also had an episode of gastroenteritis causing AKI.

So here she is seven years later at the age of 83, despite coming very near end stage renal failure, and pretty well. The management of myeloma has been transformed in the last couple of decades by the successive introduction of new drugs which aren’t so toxic. The response to treatment is probably the most striking prognostic feature in myeloma in general these days, and certainly in how well they do with kidney function.

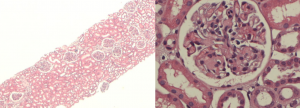

Click here for a larger image

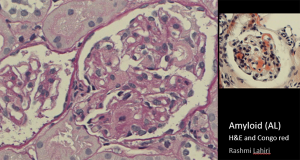

This is a completely different abnormality, on the left you can see the low power of a patient who presents with nephrotic syndrome. From a distance, you might wonder whether there’s very much wrong at all, the tubules certainly are not severely affected. There’s certainly no myeloma kidney, the topic of the day. But when you look at the glomeruli more closely, there’s too much pink. In fact there are pink blobs. There are not extra cells, but there is too much matrix, and something has been deposited and it’s got a funny color. It’s paler than the normal matrix of the kidney.

Click here for larger image

Here’s another glomerulus with exactly the same appearance. There is an arc of this material. On the right the diagnosis is confirmed. You might suspect it on conventional histological stains, but the Congo red colouring on the right confirms it. The blobsare taking up the dye.

You can get amyloid deposition without having overt myeloma. But many patients have enough B-cell proliferation to classify as a diagnosis of myeloma. Again, the best prognostic indication is whether or not you can eradicate that clone. But even then a lot of this damage will not recover, and the patient will probably remain nephrotic for quite a long time.

Further info

- This is mostly about Cast Nephropathy, the most common way that myeloma affects the kidney. There’s more on other aspects of myeloma and related disorders and the kidney on the parent page to this talk: Myeloma, MGRS and the kidney

- There’s more a myeloma elsewhere as a haematological disease under a links either below or on the page you came to this one – medcal.mvm.ed.ac.uk – Renal

- There’s more about amyloid there too.