A 59 year old female presented to her GP with a six month history of increasing shortness of breath, mainly on exertion. She has no associated cough or chest pain. She has smoked 20 cigarettes a day for the last 40 years. She gets a number of chest infections per year. She is now struggling to get up the stairs in her house.

Breathlessness, also known as dyspnoea, is a subjective, usually distressing sensation or awareness of difficulty with breathing. It can be classified by its speed of onset:

- Acute breathlessness — when it develops over minutes.

- Subacute breathlessness — when it develops over hours or days.

- Chronic breathlessness — when it develops over weeks or months.

Contents

Acute breathlessness

May occur in people with no known underlying cause, or in those with a known chronic condition and worsening symptoms. For people with known underlying disease, it is important to ascertain whether their breathlessness is due to their condition or is an emerging new problem.

Acute and subacute breathlessness most commonly have a pulmonary or cardiac cause. Common explanations:

Pulmonary causes:

- Acute asthma/acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

- Pneumonia.

- Pulmonary embolism.

- Pneumothorax.

- Pleural effusion.

- Acute exacerbation of bronchiectasis.

- Lung or lobar collapse (caused by bronchial obstruction, or compression by cancer, an inhaled foreign body, or retained secretions).

- Acute pneumonitis.

- Upper airway obstruction (for example by a foreign body or acute epiglottitis) causing stridor.

Cardiac causes:

- Acute deterioration of chronic heart failure.

- Sudden-onset cardiac arrhythmia (for example supraventricular tachycardia).

- Ischaemic heart disease (including an atypical presentation of myocardial infarction).

- Acute valvular dysfunction.

- Cardiac tamponade.

Other causes:

- Metabolic causes (including aspirin overdose, diabetic ketoacidosis, and renal failure).

- Acute blood loss.

- Thyrotoxicosis.

- Neuromuscular disease (including Guillan-Barré Syndrome, and myasthenia gravis).

- Hyperventilation (often due to anxiety).

Chronic breathlessness

Most commonly has a pulmonary or cardiac cause.

Pulmonary causes

Key explanations include:

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and bronchiectasis.

- Interstitial lung disease (including asbestosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis)

- Recurrent pulmonary embolism.

- Pleural effusion.

- Pleural infiltration by mesothelioma.

- Lung cancer.

- Cystic fibrosis.

- Occupational lung disease.

Cardiac causes

Mostly via heart failure, key explanations include:

- Hypertension.

- Ischaemic heart disease.

- Cardiomyopathy.

- Valvular heart disease.

- Cardiac arrhythmia.

- Congenital heart disease.

Other causes

- Anaemia.

- Hypothyroidism.

- Chest wall disease (including ankylosing spondylitis).

- Diaphragmatic splinting (due to obesity, pregnancy, or ascites).

- Hypoventilation (caused by neuromuscular conditions such as Guillain–Barré syndrome or motor neurone disease).

Individual conditions

Silent myocardial infarction

- Risk factors — coronary artery disease, smoking, high blood lipid levels, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, family history.

- Atypical presentations of myocardial infarction such as isolated breathlessness are more common in the elderly, in women and in people with diabetes, chronic renal disease and dementia.

- Symptoms — breathlessness, general malaise, sudden collapse, upper body discomfort, nausea.

- Signs — breathless (sometimes), abnormal pulse rate, sweating, reduced peripheral perfusion, hypotension.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) — features suggestive of acute MI include ST depression with Twave inversion, persistent ST elevation, or new left bundle branch block. Q-waves do not give an indication of the age of an MI as remain permanent following infarction.

Cardiac arrhythmia

- Risk factors — heart failure, valvular heart disease, ischaemic heart disease.

- Symptoms — palpitations, breathlessness, chest pain, syncope (or near syncope).

- Signs — bradycardia or tachycardia.

- ECG — diagnosis of arrhythmia relies on ECG obtained during the arrhythmia.

- Typical ECG features of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) include regular narrow QRS complex tachycardia and a rate greater than 100bpm. Wide complex tachycardias may have a supraventricular or ventricular origin.

Acute pulmonary oedema

- Risk factors — chronic heart failure, ischaemic heart disease, valvular heart disease.

- Symptoms — severe breathlessness, orthopnea, coughing (rarely with frothy blood-stained sputum).

- Signs — elevated jugular venous pressure, gallop rhythm, inspiratory crackles at lung bases, and (occasionally) wheeze. Peripheral circulation is shut down.

Cardiac tamponade

- Risk factors — trauma, autoimmune disease, malignancy, myxoedema, myocardial infarction.

- Symptoms — breathlessness, collapse.

- Signs — tachycardia, pulsus paroxodus, engorgement of neck veins and face peripheral cyanosis shock.

Chronic heart failure

- Risk factors — advanced age, hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, chronic cardiac arrhythmia, diabetes, obesity, family history of cardiomyopathy or premature coronary heart disease.

- Symptoms — fatigue and breathlessness, including orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea, reduced exercise tolerance, ankle swelling.

- Signs — basal crackles, displaced apex beat, third heart sound, increased jugular venous pressure, peripheral oedema, weight changes, hepatojugular reflex and hepatomegaly.

Asthma

- Risk factors — personal history of rhinitis or eczema, or family history of atopy or asthma.

- Symptoms — wheeze, breathlessness, chest tightness, cough. Symptoms are variable (often worse at night, first thing in the morning, and upon exercise or exposure to cold or allergens, or after taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication or beta-blockers).

- Signs — during an acute episode, the respiratory rate is increased, and wheeze is usually present.

- Peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) is reduced during an acute episode.

Acute asthma is:

- Life-threatening — when PEFR is less than 33% of predicted, or any of the following are present: oxygen saturation of less than 92%, hypotension, cyanosis, poor respiratory effort, a silent chest, exhaustion, arrhythmia or impaired level of consciousness.

- Severe — when PEFR is 33–50% of predicted, or any of the following are present; respiratory rate of 25 breaths per minute or greater, a heart rate of 110 beats per minute or greater, or an inability to complete full sentences.

- Moderate — when PEFR is 50%-75% of predicted, without any features of severe or life-threatening acute asthma.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- History — typically, the person is older than 35 years of age, is a smoker (or past smoker) and reports slowly progressive breathlessness.

- Symptoms — persistent progressive exertional breathlessness that is often associated with wheezing and a cough (productive of sputum). Acute exacerbations of symptoms are common, and are frequently caused by respiratory tract infection. Frequent winter ‘bronchitis’ may be described.

- Signs — there may be no abnormal signs but wheeze, hyperinflated chest, purse lip breathing or cachexia may be present. There may be signs of right-sided heart failure in people with severe disease, including swollen ankles and increased jugular venous pressure (JVP). New-onset cyanosis and/or peripheral oedema, marked dyspnoea, tachypnoea, purse lip breathing, accessory muscle use and acute confusion are suggestive of a severe exacerbation. Crackles may be present when exacerbation is infective.

Pneumonia

- Symptoms — cough associated with at least one other symptom of breathlessness, sputum production, wheeze, or pleuritic pain.

- Signs — any focal chest sign (such as dull percussion note, bronchial breathing, coarse crackles, or increased vocal fremitus/resonance) plus at least one systemic feature (such as fever/sweating or myalgia), with or without a temperature greater than 38°C. There may be signs of an associated pleural effusion.

- Note that these features may be absent, particularly in the elderly.

Pulmonary embolism (PE)

- Risk factors — immobilization, surgery, cancer, acute medical illness, obesity, prolonged travel, symptoms or signs of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), previous DVT, thrombophilia, or age over 60 years.

- Symptoms — acute-onset breathlessness (in 73% of people with PE), pleuritic pain (66%), cough (37%), haemoptysis (13%). Severe cases may lead to dizziness or syncope.

- Signs — tachypnoea of 20 breaths per minute or greater (in 70% of people with PE), crackles (51%), tachycardia (30%), signs of DVT (11%). Hypoxia, pyrexia, elevated JVP, widely split second heart sound, tricuspid regurgitation murmur, pleural rub, hypotension and cardiogenic shock may also occur.

Pneumothorax/tension pneumothorax

- Risk factors — smoking, age and body type (adults who are young, tall, and slim), previous pneumothorax, chronic respiratory disease (such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma), trauma to chest wall (including therapeutic procedures such as injections and aspirations).

- Symptoms — collapse, sudden-onset pleuritic pain, breathlessness.

- Signs — reduced chest wall movements, reduced breath sounds, reduced vocal fremitus, and increased resonance of the percussion note on the affected side. Tension pneumothorax can result in a rapid development of severe symptoms associated with tracheal deviation away from the pneumothorax, tachycardia, and hypotension.

Pleural effusion

- Causes — heart, liver, or renal failure, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, cancer (including mesothelioma), tuberculosis, pleural infection (empyema), and autoimmune disease.

- Symptoms — progressive breathlessness, pleuritic pain and symptoms of the underlying condition.

- Signs — reduced chest wall movements on the affected side, stony dull percussion note, diminished or absent breath sounds, decreased tactile vocal fremitus/vocal resonance and bronchial breathing just above the effusion. There may be signs of the underlying condition.

Lung/lobar collapse

- Causes — airway compression (for example by enlarged lymph nodes caused by cancer or tuberculosis) or blockage (secondary to pneumonia or an inhaled foreign body).

- Symptoms — breathlessness, cough.

- Signs — reduced chest wall movement on the affected side, dull percussion note with bronchial breathing, reduced or diminished breath sounds, reduced or absent vocal resonance, mediastinal displacement towards the lesion.

Bronchiectasis

- History — suspect in people with a history of recurrent or chronic productive cough, especially if they do not smoke.

- Symptoms — cough with daily sputum production (present in 75–100% of adults), progressive breathlessness (72–83%), haemoptysis (51–45%), non-pleuritic chest pain between exacerbations (31%).

- Signs — coarse crackles during early inspiration that are heard in the affected areas, usually in the lower lung fields (70% of adults). Others include wheeze (34%) and large airway rhonci (44%). Finger clubbing occurs infrequently.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD)

- Causes — include idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, sarcoidosis, pneumoconioses, ILD associated with drug therapy, ILD associated with connective tissue disease, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis/extrinsic allergic alveolitis (following sensitization to inhaled environmental allergens; for example from birds, hay, or mushrooms).

- Symptoms — cough and slowly progressive breathlessness. When it is caused by extrinsic allergic alveolitis there may be a history of recurrent episodes of flu-like illness following exposure to the responsible allergen. There may be symptoms of the underlying cause (for example joint pains when the ILD is associated with connective tissue disease).

- Signs — there may be none in sarcoidosis. When present, there may be fine end-inspiratory crepitations (indicative of fibrosis), finger clubbing, cyanosis, and signs of right heart failure.

Lung or pleural cancer

- Risk factors — smoking, asbestos exposure.

- Symptoms — cough, shortness of breath, haemoptysis, chest pain, weight loss, appetite loss, fatigue, hoarseness, persistent chest infections, symptoms relating to bone or brain metastases.

- Signs — chest examination is often normal but there may be unilateral wheeze, decreased breath sounds, or signs of pleural effusion. Other signs include finger clubbing, and supraclavicular or cervical lymphadenopathy.

Anaemia

- Symptoms — mild anaemia may be asymptomatic or cause mild fatigue. As it progresses, faintness/dizziness, exertional breathlessness, palpitations and chest pain can occur. Rapid blood loss may present with collapse.

- Signs — paleness (for example of the conjunctiva or palms). More severe anaemia may lead to tachycardia or cardiac failure.

Diaphragmatic splinting

Due to ascites, obesity, or pregnancy

- Symptoms — chronic breathlessness that develops in association with increasing abdominal size. There are no symptoms to suggest other causes of chronic breathlessness.

- Signs — ascites (shifting dullness and fluid thrill) or obesity. There are no clinical features of other causes for chronic breathlessness.

- History — there may be a history of anxiety, panic or phobia.

- Symptoms — breathlessness is often described at rest rather than being exertional in nature. Other symptoms, such as palpitations, paraesthesia, dizziness, chest pain and choking sensation may occur. Anxiety and feelings of fear may accompany breathlessness.

- Signs – no signs of a physical cause for breathlessness. Hyperventilation accompanied by sighing, tachycardia and raised blood pressure (which settles) may occur.

Management

In the acutely unwell patient:

Perform an initial Airway, Breathing, Circulation assessment. Determine the need for emergency admission by assessing the person’s blood pressure, pulse, respiratory rate, temperature, level of consciousness, peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR), oxygen saturation, and (if possible) electrocardiogram (ECG).

Arrange emergency admission for:

- Suspected asthma and any features of a severe or life-threatening acute asthma attack.

- Clinical features of a pulmonary embolus or pneumothorax.

- Rapid onset or worsening of symptoms of suspected heart failure.

- Suspected sepsis

- ECG suggesting a cardiac arrhythmia or myocardial infarction.

- Consider hospital assessment for all people with suspected community-acquired pneumonia and a CRB65 score of greater than 0.

For those who do not require acute admission:

Ask about:

- Duration, pattern and severity of breathlessness.

- Symptom change with position, for example, when lying flat (orthopnoea).

- Presence of: fever, cough, chest pain, palpitations, wheeze, any changes to voice.

- History of conditions such as cardiac or pulmonary disease, venous thromboembolism or anxiety.

- Pregnancy.

- Medications, for example, asthma may be exacerbated by beta blockers.

Carry out a general, cardiovascular and respiratory examination.

In the acutely breathless patient look for clinical features of:

- Acute asthma, especially in people with wheeze or cough that is worse at night, or upon exercise or exposure to allergens.

- An acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), especially in people older than 35 years of age who smoke (or who have smoked), particularly if they have wheeze and a new or worsening cough.

- Pneumonia, especially in people with a cough and at least one other symptom of sputum, wheeze, fever, or pleuritic pain.

- Lung/lobar collapse, especially in people with a history of cancer with lymph node involvement, tuberculosis, an inhaled foreign body, or debility causing retained airway secretions.

- Pleural effusion, especially in people with: heart, liver, or renal failure, cancer, tuberculosis or pleural infection.

- Anxiety-related breathlessness, especially in people who have no clinical features of a physical cause for breathlessness.

In the chronically breathless patient look for clinical features of:

- Heart failure, especially if the person has a history of ischaemic or valvular heart disease, hypertension, or the onset of chronic cardiac arrhythmias (such as atrial fibrillation).

- Asthma, especially in people with episodic wheeze or cough that is worse at night, or upon exercise or exposure to allergens.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), especially in people older than 35 years of age who smoke (or who have smoked), particularly if they have exertional breathlessness, chronic cough, regular sputum production, frequent winter ‘bronchitis’ or wheeze.

- Bronchiectasis, especially in non-smokers with chronic progressive breathlessness that is associated with either a chronic productive cough or recurrent chest infections.

- Interstitial lung disease, especially in people with a history of exposure to asbestos, dust (such as coal dust), birds, hay, or mushrooms.

- Pleural effusion, especially in people with: heart, liver, or renal failure; cancer; tuberculosis; or pleural infection.

- Abdominal splinting secondary to obesity or ascites.

- Anaemia.

Manage the underlying cause of breathlessness.

The patient had a thorough examination and was noted to have O2 saturation of 95%, decreased air entry throughout and emphysematous changes in her CXR. Her spirometry showed an obstructive picture and the patient was given a diagnosis of COPD. She was started on the recommended treatment and has found that her breathing has improved. She has also been referred on to smoking cessation class and pulmonary rehabilitation.

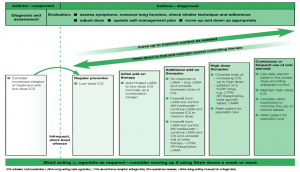

SIGN/British Thoracic Society Guidelines for management of Asthma 2016

References

https://cks.nice.org.uk/breathlessness

SIGN/BTS guideline on asthma. https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/qrg153.pdf

0 Comments